Contrasts

Gratitude for Our Caretakers

I’ve experienced poverty, assault, theft, discrimination, even occasional food insecurity. And I’ve emerged not without scars, but certainly into much better circumstances. I am fortunate today to live an upper middle-class life in a beautiful place where I want for nothing.

My children, like me, have struggled to attain comfortable lifestyles and satisfying careers despite humble beginnings. While we all had ‘hard times’ compared to our peers, we had access to “the ladder.” Why? Because we’re white. Yes, we’ve pulled ourselves up from our bootstraps, but we had some bootstraps...they were white.

I had a recent, joyful family gathering where I was blessed to share time, food, wine and endless entertainment with loved ones. And, once the house was deafeningly silent of their joyful noise, I attended a documentary film. It was curated by local cinephiles at an Island film festival – yes, this place is posh enough to host a top-quality film fest.

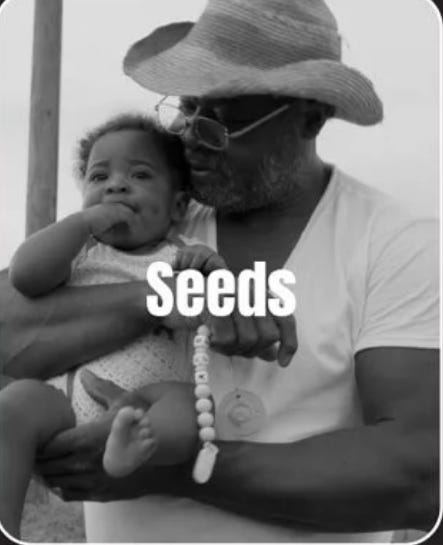

This particular film was billed as “A look into the lives of Black generational farmers, unveiling the challenges of maintaining legacy and the value of land ownership.” The filmmakers were all Black women, and nothing prepared me for the story they told, especially the way they told it.

In black and white, these women drew me deeply into the lives of a group of Black farmers in Georgia. This was no arm’s length observation of Black farm life. It was a carefully crafted and intimate immersion into their homes and churches, their dawn to dusk HARD work every day and, most of all, their dignity. I felt as if I’d been in the home of the great grandfather who was farming 72 acres while supporting his granddaughter and her family on $900 a month, his social security check. He was a creative genius who never wasted even a Styrofoam cup if it could be used to repair a tractor tailpipe. He pulled a cabinet from a junked trailer and repurposed it into the house he was building for his granddaughter.

I was moved by the Grandad’s love for his bright little great granddaughter. He slipped easily from the arduous task of bolstering his house with concrete blocks – a promise broken by his white contractor -- to rocking his infant great grandson lovingly to sleep. He and his fellow farmers harvested watermelon one at a time using a relay to load each precious fruit onto a truck for delivery to buyers.

He was not unique in this tightly knit community of farmers who love their land and define the term ‘struggle’ in their efforts to obtain the same government subsidies afforded to their white counterparts. Others in this community descended from enslaved cotton pickers were harvesting cotton by machine, plucking the tufts with another expensive machine they owned communally and packing them into bales as large as container cars. They did this work literally from dawn to dusk. Their hands were deeply wrinkled and bent with arthritis. Their skin was rugged from constant exposure to sun and wind. Yet they laughed with each other and went about their work, herding cattle on horseback, ploughing deep furrows in rugged ground to plant, and helping each other to manage their sick and infirm without complaint.

Their one complaint was to a government that had promised to unlock racially restricted funds to help them get the seeds they needed to plant those furrows at the proper time. They complained about a government that had delayed the subsidies they desperately needed to keep their family farms and to raise future generations with the values of hard work, integrity and love for the land. At the time of the filming, they were – as a group – lobbying their legislators for Black farmers’ access to the Dept. of Agriculture’s promised subsidy fund for farmers.

By the end of the film, I felt I was part of that community. I felt a sense of the shared responsibilities I saw in them. Somehow those filmmakers wrenched me from my outsider position into their lives.

I left speechless in the daylight. The last thing I wanted to see was a bunch of privileged white people, which is exactly what I found as I exited the dark theatre. At that point I would have liked to slip out of my white skin into something more genuine...like those Black farmers’ lives.

The contrasts between my world and theirs are extreme and systemically perpetuated by design. Yet I believe those black farmers could teach me so much about living with joy, about growing where we’re planted, and about unconditional love. I am also so deeply aware that it is people like those Georgia farmers in SEEDS (the film’s title) who make my privileged life possible. Those Black farmers, immigrant workers, other black and brown people are behind my every convenience. They deserve everything we can give them because without them, we are much less.

This will be my last submission for two weeks while I travel. Back again August 25. Happiness and good health to all.

So relatable! Excellent writing…drew me in…